Tending To Your Tendons: Part 1

Climber’s elbow. Achilles pain. Rotator cuff tear.

Most athletes have experienced tendon pain at some point in their careers. In fact, tendon pain is one of the most commonly diagnosed chronic connective tissue disorders in sports medicine.(1) Minor injuries to tendons will resolve quickly by themselves, while complete tendon ruptures typically require surgery to manage the repair process. In between these extremes lies a population of athletes with tendon injuries that take unbearably long to resolve and may never heal normally.

Why endurance athletes are likely to develop chronic tendon injuries:

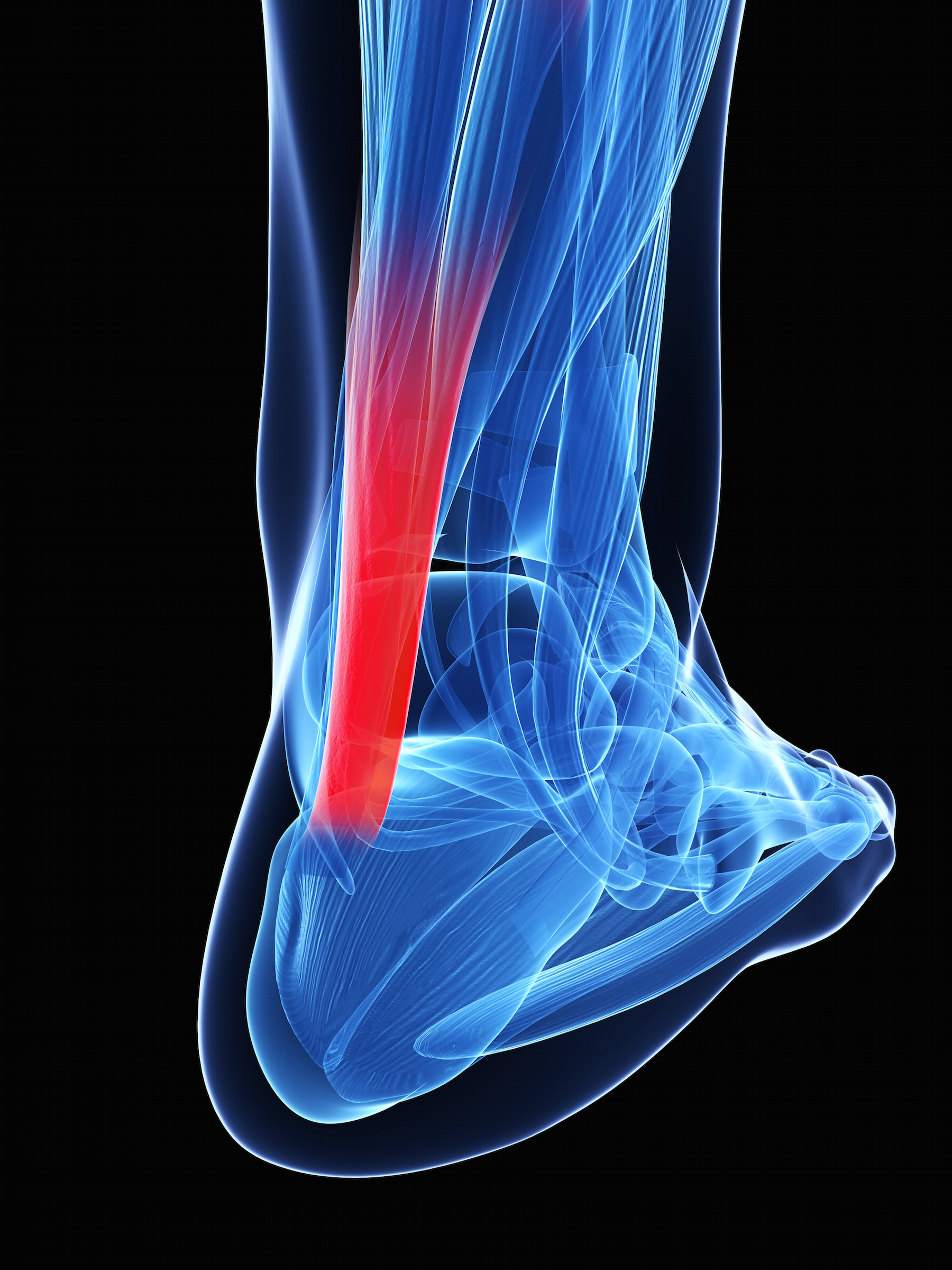

A tendon is a type of connective tissue that transmits forces generated by muscle to the bone; tendons store and release energy to propel the body forward, sideways, backward, etc. Connective tissues like tendons adapt at a much slower rate than muscles do. Muscles heal quickly because they are nourished directly by a rich blood supply; tendons have a poor direct blood supply and are fed mostly through the synovial fluid-containing sheath surrounding the tendon. Endurance athletes often increase the intensity and length of their workouts at a pace too fast for connective tissue to adequately adapt. Their muscles may be able to handle the increased workload, but their connective tissue (tendons, ligaments, bones) can’t keep up and injury results.

Microanatomy of the injury: tendonitis vs. tendinosis

Tendon pain is often diagnosed as tendonitis, which is by definition an inflammatory condition. This is frequently an improper diagnosis. In the period immediately following a tendon injury, there may indeed be a true inflammatory response of the tissue surrounding the tendon.(2) This tissue is vascularized and thus can become inflamed. However, there is significant debate in the scientific community over whether tendons themselves are even capable of inflammation.(3,4) Remember, they have a poor direct blood supply. Chronic tendon pain is usually due to degeneration, not inflammation; it is therefore better classified as tendinosis or tendinopathy.* Tendinosis results when a tendon fails to heal correctly because of repetitive reinjury, a poor environment for self-repair, vulnerable anatomy, and possibly the injudicious use of cortisone shots.

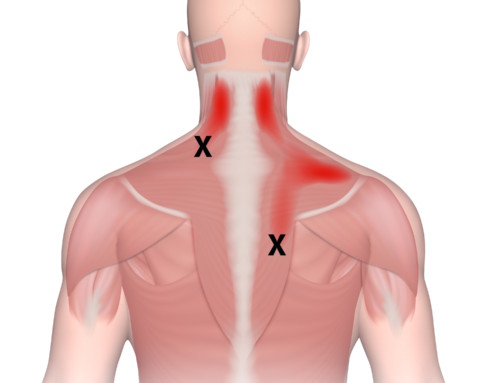

There is a real difference here. If you were to cut yourself open and take a look at your connective tissue, a healthy tendon would appear bright, glistening, and white; a degenerated tendon would appear dull and gray. Under a microscope, your tendon should look like a bundle of straws, as healthy collagen fibers are aligned in the same direction. Tendinosis, on the other hand, resembles a field of debris containing unconnected collagen strands and fragments of material with no pattern of tendon structure.(5) Tendinosis is often swollen and tender, but it typically lacks the increased warmth and erythema characteristic of a true inflammation.

Why this matters to endurance athletes:

If your injury is chronic, chances are, you are dealing with tendinosis NOT tendonitis.

Tendonitis is treated as an inflammatory injury. This means doctors will prescribe anti-inflammatories such as NSAIDs, ice, or corticosteroid injections. Such therapies aimed at reducing inflammation (in the absence of inflammatory cells) are contraindicated because they further degrade the tendon.(6) In fact, research shows that tendons become weaker following steroid injection, and may even be more likely to rupture in the future.(7,8)

So, what’s an injured athlete to do?

Check Out: Tending To Your Tendons: Part 2, in which I cover the three things ALL endurance athletes need to be doing to restore the integrity of their tendons and to prevent the occurrence of future injuries.

* Of course, I am simplifying things a bit here. It is possible that drawing such a stark dichotomy between tendinosis and tendonitis is artificial, and there is some evidence to suggest that—like most things—tendon dysfunction occurs on a continuum.(9) Certain cases of tendinosis may have some elements of inflammation, and pockets of both inflammation and degeneration may coexist along the same tendon. Regardless, the point remains that using anti-inflammatory measures as a blanket treatment for all tendon pain will damage the wide spectrum of tendinous injuries that are characterized more by degeneration than by inflammation.

References:

1. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services “National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey 1998‐2006.” National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention2.

2. O’Connor, F. G., Wilder, R. P., & Nirschl, R. (2001). Textbook of running medicine. McGraw-Hill; 42.

3. Dicharry, J. (2013). Anatomy for Runners: Unlocking Your Athletic Potential for Health, Speed, and Injury Prevention. Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

4. Rees, J. D., Stride, M., & Scott, A. (2013). Tendons–time to revisit inflammation. British journal of sports medicine, bjsports-2012.

5. O’Connor, F. G., Wilder, R. P., & Nirschl, R. (2001). Textbook of running medicine. McGraw-Hill. 41.

6. Khan, K. (2003). “The painful nonruptured tendon: clinical aspects”. Clin Sports Med, 22: 711– 725

7. Dean, B. J. F., Lostis, E., Oakley, T., Rombach, I., Morrey, M. E., & Carr, A. J. (2014, February). The risks and benefits of glucocorticoid treatment for tendinopathy: A systematic review of the effects of local glucocorticoid on tendon. In Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism (Vol. 43, No. 4, pp. 570-576). WB Saunders.

8. Nichols, A. W. (2005). Complications associated with the use of corticosteroids in the treatment of athletic injuries. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 15(5), E370.

9. Cook, J. L., & Purdam, C. R. (2009). Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathy. British journal of sports medicine, 43(6), 409-416.